The measure of performance of this project is not primarily the accuracy of the system's internal model of the world, although that is an important concern when considering the scalability of solutions to larger systems. The accuracy of this representation is only important with respect to its ability to realize an appropriate externalized behavior. The intelligence of the system must be sophisticated enough to deliver the desired action, but no more. Rather, the system must be judged by how well it follows human activity as an automatic camera operator for the given surveillance or videoconferencing application, according to the subjective opinion of the human viewer. Fortunately, this set of control requirements has significant overlap with the system's goals of resolving uncertainties about the state of objects in the world. For example, a shift in conversation to a new speaker out of camera view will inspire the controller to investigate it visually, an action which corresponds with the human viewer's desires as well. The differences between the qualities of exploratory motion and desired application behavior typically involve the speed and frequency of saccadic motion. A human or robot may achieve optimum understanding of the world by rapidly and frequently re-orienting its vision toward different parts of a scene. Such behavior by a videoconferencing or surveillance camera would not be pleasing to the human viewer; rather, the camera motion desired would be more conservative, zooming out when uncertain where the action is, and zooming in only when confident that the important activity is likely to stay in the detected location. A compromise must therefore be reached when designing the speed of movement behaviors.

In many video studios, multiple cameras may be aimed independently, and the broadcast signal switched between them when appropriate. This allows exploratory "through-the-viewfinder-search" motion by one camera when off the air, while another camera stays fixated on the current target. The result of this strategy is more pleasing to the human viewer than video recorded by a single moving camera, such as in home-movies, or television shows like "Cops." For the current application, however, only one moveable camera is budgeted, so motion in the camera view is inevitable.

Design of a control behavior to follow human conversation requires knowledge of conversation characteristics, such as the average frequency of changes between speakers. Sellen [122] studies speaker switching time, speaker overlap, and interruptive speech behavior during same-room and video-enabled conferencing. Canavesio and Castagneri [123] describe automatic camera-switching techniques in videoconferencing based on speech patterns. These works and other empirical performance observations may be used to develop appropriate control behaviors for the camera system.

A good videoconferencing camera controller should be able to zoom the camera view in on the person speaking, move between speakers, and zoom out appropriately for viewing multiple people when it is not clear which person is the most important. In the previous chapter, behaviors for looking in the direction of a sound source and viewing a speaker's face were developed. What is still needed is a behavior for viewing multiple faces. Figure 74 illustrates the relationship between behaviors that may be fused for videoconferencing control.

Figure 74: Behavior Components for Videoconferencing

Aiming the camera at a single face involves the crisp choice of a single tracked target, but viewing multiple faces requires weighted compromise among multiple objectives. A fuzzy centroid-based control scheme may be used for deciding camera direction for this purpose. As described in Chapter 7, the danger of using centroid defuzzification is that a compromise between competing objectives may not satisfy any of the objectives, e.g., the camera may be pointed at an empty space between two people. When such a situation occurs, it is important to detect the inadequacy of the compromise and take appropriate recovery actions. For camera control, the appropriate response to conflicting target objectives is to zoom out to a wider field of view. A strategy for deciding just how far to zoom out is developed below.

Figure 75: Geometry of Face Width Angle

Each person being tracked by the sensor system will have an estimated position which may be transformed into the camera's polar coordinates, determining the pan and tilt angles required to center that target in the frame. The zoom may be calculated from the target distance d such that the person's face will occupy the desired percentage of the width of the image. Figure 75 shows the geometry of the face in determining field of view. The angle occupied by the width of the face from the cameras' perspective is calculated as

![]()

where w is the width of the face, which may be estimated at about

0.2 m. The camera zoom (in terms of field-of-view radians) optimized

for viewing that face will be KF![]() ,

where KF specifies the desired ratio between the total image width

and the face width in the resulting view.

,

where KF specifies the desired ratio between the total image width

and the face width in the resulting view.

A compromise among the different pan, tilt, and field-of-view angles specified for each target may be reached by considering the relative interest in each target and performing a weighted average through fuzzy rules. The fuzzy rule applied to each target will incorporate expert knowledge through qualitative terms, and may look something like:

IF ( targeti is noisy and targeti is well_established and targeti is nearby )

THEN ( pan is pani; tilt is tilti; fov is fovi )

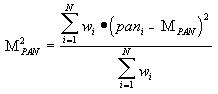

where the terms noisy, well_established, and nearby are fuzzy sets defined for the sound level, path age, and proximity of each target being tracked. As described in Chapter 7, these terms in the antecedent of the rule define a weight, wi, for the specified output during the centroid operation. The resulting pan and tilt angles, for example, become the first moments of the distribution of rule recommendations, calculated as

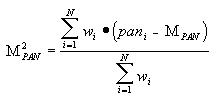

The problem with this approach is that the weighted average of pan locations may define a pan angle aimed at empty space between targets, while the field-of-view output may be specified too narrow to see them. The strife associated with incompatible rule recommendations may be quantified using the second moment of the pan control rules:

The square root of the second moment provides a measure of how far apart the targets in the distribution are, which may be incorporated into the field-of-view command as:

![]()

Using this strategy, the camera controller will zoom in on a particular target when the importance of that target dominates, e.g., that person is the only one speaking. When multiple people are speaking or are otherwise strongly weighted, the camera will center on the group and attempt to zoom out and view the group as a whole. If the recommended field of view is larger that the widest possible zoom setting, however, the winner-take-all single-face tracking behavior may be invoked to center the camera on the strongest target.

Figure 76 shows the camera following a conversation in a videoconference setting. After the first speaker stops talking and the second begins to speak, the camera zooms out and pans to find the other speaker. Both faces appear in the view at the same time while the controller attempts to compromise between what it perceives to be two equally important targets. Once the first speaker has been silent long enough, the second speaker dominates the conversation and the camera zooms in.

Figure 76: Camera Behavior for Videoconferencing

In this experiment, only the local room occupants spoke, but in a real video conferencing environment, the sound of remote party's voice would be played into the room through a one or more loudspeakers. This would require the audio processor or control system to have access to the remote audio feed in order to tell when the sound was not coming from the local room; otherwise, the camera would attempt to look toward the loudspeaker! Most two-way videoconferencing system include echo/feedback suppression processing to remove sound from the loudspeakers that re-enters the microphones on each end. Such processing could be extended to assist the separation of local audio from remote audio for the requirements of local sensing.

Computer vision is growing in popularity for security applications [124,108]. Such systems can monitor remote sites with a minimum of personnel. When unauthorized activity is detected, the system can notify a human operator and record video of the events. The ability to automaticaly follow and zoom a camera in on the subject of interests provides better quality video information for identification by the computer or human beings who may view the recorded content later. The body tracking system developed previously was configured to demonstrate this application.

The camera-control behaviors required for surveillance are almost identical to the videoconferencing behaviors described earlier. The only difference is the video processing, which uses image difference rather than skin color detection. Since targets may be further away than in videoconferencing and a large field of view must be monitored, limited camera resolution and processing power makes face detection more difficult. Also, subjects may cover their faces, and the rest of their body may be important to capture within the frame. For these reasons, image difference using the wide-angle camera was used to detect activities visually, and the pan-tilt-zoom camera was used to follow the subject in the room. Sound information was also be used to point the camera in the direction of targets when no useful visual information was available. Figure 77 shows the relationship of behaviors for surveillance tracking.

Figure 77: Behavior Integration for Surveillance

Figure 78 shows the camera controller as it follows a person walking into and out of a room. Images from the stationary wide-angle camera were used to detect the person by using reference image difference, while the pan-tilt-zoom camera moved to keep the target in view. Using a stationary camera with a fish-eye lens for the vision task greatly simplifies the processing required to detect and track moving targets, and allows a large area of the room to be sensed simultaneously.

Figure 78: Camera Tracking Motion for Surveillance

Computers which can percieve and track human activity have much more information the real world they inhabit than do most existing machines. The opportunity to develop much more user-friendly applications will benefit from these basic perceptual capabilites. Future areas of research and potential applications are described below.

The matching of sound localization data with face location provides the ability to associate speech samples with the face and location of the speaker. A speech recognition system may then process dictation tasks or follow spoken commands with sensitivity to the context of the speaker's identity and location. Computer understanding of conversations among multiple people, for example, would require the ability to distinguish speaker transitions. This requires close time registration between the sound localization and speech recognition processes, which is possible when both tasks operate together on the same personal computer. Association of speech and faces may also assist in identification of people through joint use of voice and facial characteristics.

If a computer is given the ability to identify and distinguish between people as described above, then a new level of human-computer interaction becomes possible. The computer would be aware of discrete human beings in the world, and would be able to track their movements and activities in the room. It could then communicate with people on a more personal level, tailoring its behavior to each individual's name, sex, occupation, and seniority within a group, depending on what information it is provided with. For example, the computer could be given a sequence of conflicting commands like "Look at Bob," "No, look at her," and "Look at me." The computer's actions would depend on the locations, names, seniority, and sex of the participants.

The use of digital control networks for home, office, factory, and automobile automation is rapidly increasing at the time of this writing. Control networks can be used to operate lighting, doors, windows, entertainment systems, telephones, thermostats, security systems, and manufacturing equipment. The ideal user-friendly interface to such a network would be capable of accepting verbal commands and interpret people's needs based on context. For example, a disabled person could give the command "open," and the computer would interpret the command appropriately depending on whether the person is in front of the door or window blind. Numerous verbal commands such as "start," "stop," up," and "down" could have different meanings depending on the object they are associated with. Cost would likely prevent each individual appliance from having its own intelligent speech recognition and vision capabilities, but a more centralized system could interpret user activities, associate them with objects, and send appropriate commands over the control network.

This chapter has demostrated some of the capabilities of the system developed, and has suggested ways that it may be extended into new levels of machine intelligence. The underlying thesis of this work is that intelligent sensing of people shall become a commonplace feature for nearly all personal computers, not just those used for high-end installations. As real-time video and audio data captured from the environment becomes available to personal software, these and similar applications will evolve to exploit it.